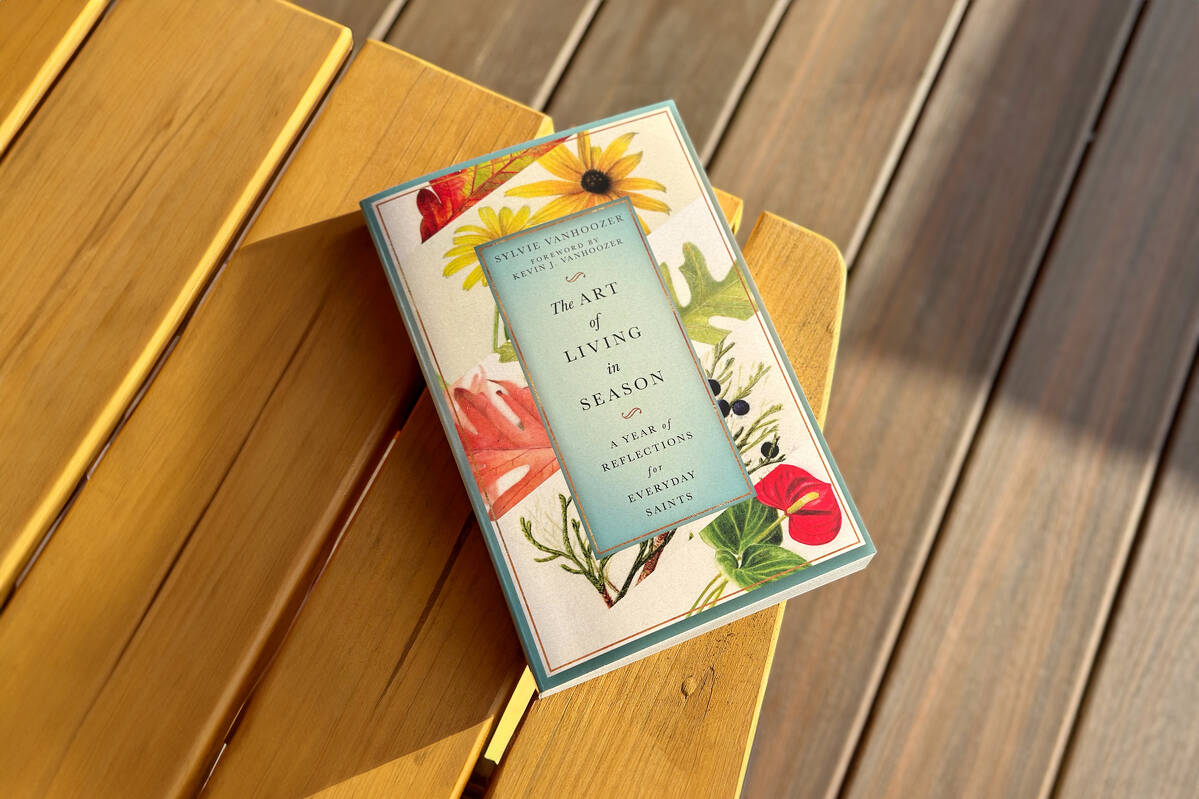

How does one tell the story of one’s life with God? Some saints have written what, for lack of a better term, we might call theological autobiographies: Augustine’s Confessions, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and C. S. Lewis’s Surprised by Joy. My wife Sylvie has just added one more book to that list: The Art of Living in Season: A Year of Reflections for Everyday Saints (published on April 9 by InterVarsity Press).

Sylvie is not a trained theologian – unless having dinner with a trained theologian (me) for over forty years qualifies her as such. And truth be told, the book she has written is not really a theological autobiography. While it does include reflections on her own Christian pilgrimage, it is also much more: it is, first and foremost, an invitation to join with her and other pilgrims in the lifelong adventure of following Jesus through the many places and seasons of everyday life. It’s a reflection on how to be an everyday disciple – a person joins up the story of one’s own life with the story of Jesus – whenever, wherever, and whatever you happen to be and be doing. It all begins in a village far, far away in southern France – Provence, to be exact – where Sylvie grew up. Instead of a Christmas manger, they have an Advent crèche, and instead of just the holy family, it is filled with clay figurines of southern French villagers, all dressed in nineteenth-century garb, for their legends say that Christ was born in Provence! What happened was this: After the French Revolution, traditional manger scenes were forbidden. Families, therefore, set up disguised manger scenes in their own homes to keep the Christmas tradition alive. It was an inspired piece of contextual theology: for dressing up the people in the manger as though they were from contemporary Provence allowed the people to see themselves –butchers, bakers, candlestick makers, and just about every other vocation you could find in a typical southern French village – as part of the story of Jesus.

Sylvie has faithfully kept her crèche and regularly sets it up in our home at the beginning of each Advent season, and over the years, her collection of figurines has grown. She has shepherds (of course), but also musicians, folk dancers, florists, carpenters, masons, farmers, and more. Each of these characters (the Provençal term is santon for “little saint”) brings a gift to the baby Jesus, a gift that has something to do with their own calling and place in life. Her crèche has become a parable of discipleship, a visual reminder that whatever our vocation, we must do it as unto the Lord, not least by offering what we do in our vocation back to Christ.

Each year, at the end of the fall semester, I invite my doctoral seminar students to the house for a Christmas party. Part of the ritual includes Sylvie giving the students a “tour” of the crèche and explaining its significance. One year, as I was looking over my course evaluations for the semester, I was surprised to see that a couple of students, when asked what was the best aspect of the course, replied, “When Mrs. Vanhoozer showed up and told us about the crèche.” That was one of the first indications that this was an idea worth developing.

I’ve long maintained that Christian doctrine serves the cause of Christian discipleship, but Sylvie’s book gets practical and shows us how. The art of living in season is really about the Christian art of living as a disciple through the seasons of the church, the seasons of nature, and the seasons of life. Her “little saints” were her inspiration. What, she wondered, would it be like to worship the Lord and bring Jesus gifts not only at Christmas (as the figures do in the manger) but throughout the year and the various seasons of our lives? The book is her answer. Each chapter focuses on a different season, a different santon (everyday saint from the manger), and a different stage of her own Christian life.

I mentioned pilgrimage earlier. The Christian life is a journey from one place to another. In marrying me, Sylvie left her beloved country only to travel through several lands: England, Scotland, and eventually the USA. She experienced homesickness, a familiar ailment in what Marc Augé calls “supermodernity,” namely, the experience of inhabiting non-places: spaces like hotels, airports, chain stores, and even suburbs that appear untethered to particular histories and identities. The challenge Sylvie set herself was how to be “at home” in Christ, no matter where she actually lived.

Many people today, especially immigrants and refugees, can identify with being displaced. Yet Christians are, in one sense, permanent resident aliens, “sojourners and exiles” (1 Pet. 2:11) who live between the times of Jesus’ first and second comings. How then shall we live between the times and through the seasons? Sylvie’s book is about how to do just that. It has to do with learning to attend to and embrace one’s location as the place where God puts and grows us. Sylvie finally made peace with living in Midwestern Illinois by coming to appreciate how the same God who created Provence also created the prairies. She took botany and art classes at the Chicago Botanical Gardens and eventually earned a certificate in botanical art. Her art – the result of paying attention to the place where God had planted her – also adorns her book. Of course, the art of living in season does not always involve painting your surroundings. Yet, disciples would do well to consider seriously how to be not only a peacemaker but a placemaker. Sylvie’s book is all about encouraging us to think about how we might help the plants, people, and churches in our local places to flourish. This is the art of living in season: knowing how to live as a God-glorifying placemaker everywhere, at all times, and with everyone.